Vue.js “3x3”: a Mental Model for Building Fast

Like many folks who choose Vue, I find it to be incredibly productive and it rarely gets in the way.

The recently released 2022 State of JS survey once again has some in the Vue community debating the merits of options vs composition API and whether the transition has held back Vue. I started to reflect on what aspect of Vue 3’s composition API made it so easy for me to be so productive with very little foot-gunning.

I think that my own productivity in Vue can be broken down to a simple “3x3” model that makes it easy to grasp and be productive while building applications without the need to think about “higher order” complexity that can create drag.

To better understand what I mean by that, both Nadia Makarevich and Amy Blankenship have fantastic writeups that outline some of the key road hazards to watch for when working with React that I’ve personally encountered as well on professional projects.

These types of hazards simply don’t exist in Vue because renders are “opt-in”. In Vue, one almost never has to think about side effects and over-rendering or optimizations requiring useMemo and useCallback because as Arek Nawo summarizes in his excellent and concise writeup, the fundamental difference between Vue and React is that they have inverted models of what gets (re-) rendered.

In this article, I want to outline a simple 3x3 model to understanding Vue.js to help you build better, faster, and with less foot-gunning. If you’d like to see the sample code, check out this repo:

We could easily build this entire application without the state or routing part as a simple one-pager and a few lines, but our goal here is to build a foundation for bigger, more complex applications.

The 3x3 Model

The topic of Vue 3 always invokes discussions around usage of reactive vs ref vs $ref and options vs composition API. There are intricate framework capabilities that support a wide variety of use cases and builds.

This is not an article about complexity (we can’t all be as brilliant and gregarious as Anthony Fu); what we want is a simple, easy to grok mental model for the Grug-Brained Developer that lets us build 90% of applications in a fast, stable, and low fuss way.

My own internal mental model of Vue is decomposed into three layers of three core concepts each or “3x3”:

- The high level building blocks: the app, the state, and the routing

- The component level building blocks: the template, the script, and the CSS

- The script level reactivity building blocks:

ref,watch, andcomputed.

We’ll explore these concepts in the context of building a simple checklist management application, but it scales surprisingly well and it’s the same foundation I’ve used to make apps like Turas.app:

1) The High Level Building Blocks

This first layer describes how logic is organized at the application level: the app, the state, and the routing.

1.1) The App

Let’s start by creating an app:

cd code

mkdir vue-3x3

yarn create vite . --template vue-ts

yarnThis creates three files of interest (coincidence??).

Here’s our src/index.html file:

Which loads src/main.ts:

Which mounts src/App.vue to the div in index.html:

We can view this app in the browser now by running:

yarn dev1.2) The State

At this stage, it’s not necessary to have global state, but beyond a prototype, you’ll find that having global state is almost always necessary to ease the pain of prop drilling (although Vue also has a provide-inject paradigm as well). In React, there are multiple models and frameworks to choose from when working with state. Some of those frameworks can also be used in Vue like nanostores or Daishi Kato’s Valtio. But Vue’s recommended state library is the excellent Pinia.

To add Pinia to our application, run the following:

yarn add piniaAnd update our application:

Pinia provides shared state using the concept of “stores” of which you can create as many as you’d like and recompose as needed for your application.

We’ll create a simple model and store in src/stores/appStore.ts:

1.3) The Routing

Routing is simply mapping URLs to views and components in our application. Vue’s recommended router is Vue Router.

yarn add vue-routerWe’ll create three components (coincidence?!?!): src/pages/Login.vue, src/pages/Index.vue, and src/components/ChecklistDialog.vue (just like the empty App.vue) and plug in our routing:

For a simple application like this, we can hook up our router directly in main.ts, but let’s create a separate file under src/router/index.ts:

And update our src/main.ts to load our router:

If we fire up our app now:

yarn devWe get our login route in the URL.

That’s the foundation of an SPA Vue application distilled to the basics.

2) The Component Level Building Blocks

We’ve already seen some of the basics, but now let’s dive into our component level building blocks: the template, the script, and the CSS.

2.1) The Template

While it is possible to use JSX/TSX with Vue, I prefer the single file component (SFC) practice of splitting the template from the logic.

Let’s add an input for a username and a button to our login page:

And this is what we get:

2.2) The Script

The script block is where we add our application logic. Let’s say we want to disable the login button unless the user enters a username. When the user clicks the button, we want to validate the username and route to our index page.

We need the following (once again, in 3 parts!):

- Bind the input to a property

- Bind the button state to the value of the property

- A function to route to the index page

Here’s the app:

What should be noted about the script block is that unlike in React, state changes do not cause a re-render of the whole component tree. Within our component the script body is only executed once.

This is a very fundamental difference between React and Vue. Here’s the same application in React (minus routing and global state):

Let’s see what happens when we type in a username in the React version:

The reactivity system of React is in fact conceptually “inverted” from Vue’s. The reason the disabled works on line 19 is because the entire component is redrawn (as Amy points out in the comments, even the checkUsername function is reallocated) with the value of username now being “hydrated” from useState() each time it is invoked on re-draw. In this trivial case, it doesn’t really matter; you’ll never notice the performance difference or odd side effects caused by an errant function invocation. But as any application becomes more complex, it is imperative to understand and manage this lifecycle; the bigger the app and team, the harder it is to do this well.

If you’re new to React or Vue, Nadia Makarevich’s excellent React re-renders guide is a must read.

2.3) The CSS

In Vue, you can include CSS directly in the .vue SFC file and it can either be scoped to the component or global.

Let’s style our input:

Two things to note:

- The

scopedattribute denotes that the CSS is only scoped to this component (important: this also means down the tree as well; child components do not get scoped CSS!). - See how we can use the values from our script in our CSS? If we wanted to make this reactive, all we need to do is declare

const spacing = ref('8px')instead!

The result:

3) The Script Level Building Blocks

While the depths of Vue’s reactivity system can be convoluted, in general, you only need to use three primitives:

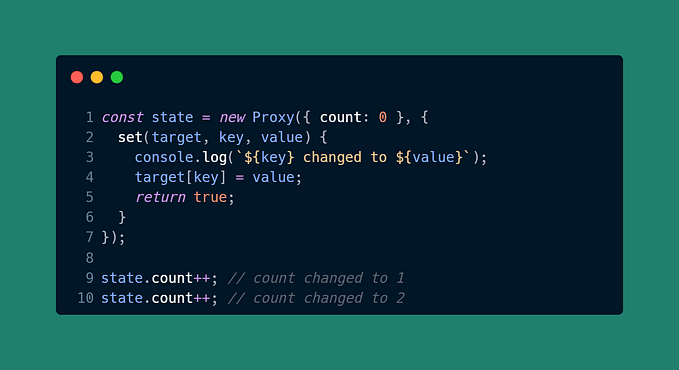

ref— we’ve already seen this in action. This is how we declare a property to be reactive.computed— this is how we create a reactive projection (think of the wayArray.mapor SQL’sSELECTstatement works to project a new shape).watch— this is how we can watch for changes in state and perform additional logic.

There are also reactive and the (now dropped) $ref transform, but using ref alone has never been an issue for me and I find it simpler to just not even worry about reactive vs ref vs $ref. Just use ref. (Turas.app is built entirely with only these three reactive primitives).

In the React world, directly mutating properties on objects in state is frowned upon. Consider Redux which works with immutable state that requires you to push the next snapshot of the state. So the use of spread and destructuring of state is common. But with Vue, this will generally create a bit more work since destructuring a reactive object then requires toRefs to make the properties reactive again. Personally, I find it easier to track where properties are “homed” or “rooted” by not destructuring state; in short: simplify your mental model and focus on just the 3 primitives.

The reactivity system of Solid.js in fact aligns very closely with these three primitives. createSignal = ref, createMemo = computed, and createEffect = watch. To me, it’s a testament to just how fundamental these 3 primitives are for any truly reactive presentation framework.

To help demonstrate these principles as well as state, we’ll expand our application a bit and fill out Index.vue to show our list of checklists and ChecklistDialog.vue where we can create/edit a single checklist.

3.1 Reactivity via ref()

We’ve already seen this in action. ref is the equivalent of React’s [state, setState] pair. But note that when we read or write the value, we need to use .value :

In the template, the value is already unwrapped for us:

3.2) Reactivity via computed()

The easiest way to think about computed is that it is a reactive projection of our state in much the same way that a SELECT is a projection of a table or Array.map allow us to project the shape of an array of objects of one shape into an array of other shapes.

Our index page shows us a list of our checklists and we can build it like this:

Here’s the state of our app:

See that disabled state? What if we want to add a computation so that we only enable it if the list name is unique? What we need is a way to project a boolean from the state of our list.

And here’s the result:

But computed is not limited to simple primitives; what if we want do display the list as a sorted and filtered list? computed again!

Our computed list projection combines a filter and a sort operation that uses the value of hidePrivate bound to our new checkbox (line 12).

Here’s how it behaves:

We can even refactor this and move the computed state to our store instead!

What’s productive about Vue’s computed is that it automatically tracks the dependencies for us and there’s no need to explicitly define the dependencies.

3.3) Reactivity via watch()

watch lets us execute some logic when the value of what is being watched changes. This is often useful when there is a need to change the state of one component based on the change of state of a component in another part of the application or when the app needs to trigger some service call to execute.

Let’s fill out our ChecklistDialog.vue component:

We’re watching on the state of the app.selectedChecklist and when it is truthy, we’ll set this dialog to be open via the visible property.

And now add it to our app:

Now here’s our simple checklist app:

We didn’t need to use watch in this example strictly speaking because we can simply create visible as a computed, but watch lets us execute other code when the value changes. We could have also passed in the selected value as a prop instead, but this creates a dependency between the component that can make it difficult to refactor our component tree. With this pattern, we can move the dialog anywhere in our tree (for example, directly in App.vue at the root).

I hope that this simple “3x3” mental model helps you better understand why Vue is such a productive front-end framework to work with and why it is my framework of choice when I have the luxury of that choice. This simple model reduces much of the complexity that teams may only need in edge cases.

When combined with the excellent Quasar Framework, it provides the ability to build fast and stable applications with minimal fuss and second-order thinking required to ensure the application can scale.

If you liked this article, give a follow, check out my other musings on React, Vue, and application development. You can also find me on Twitter @chrlschn and LinkedIn.